Making Meaning of the Madness

Chapter 1

Healing

Recognize you are unique among all others.

Your healing will occur in your way;

it may take quite some time,

but it will happen.

Journal: Feb ‘97

Very soon after Jeff died I found walking on the beach, through the forest, or just about anywhere quiet and natural provided a restful, restorative environment. Then five weeks after Jeff’s death, my father died suddenly of an aneurysm. Because of the compounded shock of those two deaths, much of my time was spent in a haze, bludgeoned and bewildered. Confusion became an overwhelming condition, a state that would stay with me for many months, and returns even now. My once-ordered life had suddenly come apart, and I was having a difficult time coming to the understanding that the quality of time left to me on earth was changed forever. Irrational thoughts came to me frequently.

I recall walking along a beach on Vancouver Island thinking to myself that here was where I belonged. I would sell the house, leave my teaching job and move with my wife Carol and our two remaining children to this beach area. We would bind ourselves together, protected from the elements of life and just walk the beach for however long it took to get through our misery. I didn’t follow through on those thoughts, but I certainly understand people who act impulsively under stress, groping and seeking any form of release.

Healing occurs at a different pace and in different ways for everyone. My healing has assumed a number of forms: baking bread; taking a greater interest in gardening; realizing that I need to look after me (that thought took some working through); finding a new world in computers; cultivating new friends; writing.

More than anything else, I needed time to reflect—to reflect on Jeff’s life, his death, and the staggering reality of saying goodbye.

My journal, some poetry and a biographical sketch of Jeff occupied much of my time in a very constructive manner. I found I was communicating with my son and with myself. Writing gave me an opportunity to be with Jeff in a spiritual sense, and it gave me an opportunity to come to grips with my situation and to know myself better than I ever had, some of which I didn’t like. I needed a conversation outlet, but being a fairly private individual, I found it difficult to convey my truest feelings to others. Writing provided the opportunity.

Strange how life is. Before Jeff’s death I seldom engaged in conversations of the soul, but immediately upon losing him, I had a tremendous need to do so. While a few men were able to share my grief, I found many could not, any more than I could have mere days earlier. They avoided the subject entirely. Talking with some women became a release, but logistically, often that wasn’t possible. So I found my greatest outlet and comfort in writing.

There were thoughts and feelings that cried for release. At times I questioned my need to write some of the things I did, but I know now how necessary to my general well being those writings were. Not all of it was pleasant, but all of it was therapeutic. Even if none of my other advice or experiences have meaning for the people who read this book, I cannot emphasize strongly enough the benefits I found in writing, especially journal writing. For the first year I wrote almost daily, sometimes for hours at a time. After the first year the entries became less frequent, but they continue to be a very positive thing I do for myself.

I learned to pay attention to beautiful, smaller things: foaming whitecaps on a grey and pounding sea; a red fox streaking across a stubble field on an early winter morning; sunrises; a seagull flying overhead as the setting sun glanced off the whiteness of his underbelly contrasting him against the darkening sky; full moons; a kayak gliding through a kelp bed; baby grasshoppers emerging amidst the cacti on a dry prairie hillside; butterflies; a blue heron doing sentinel duty in a West Coast tidal pool. Their solitude, their silence, were sanctuary.

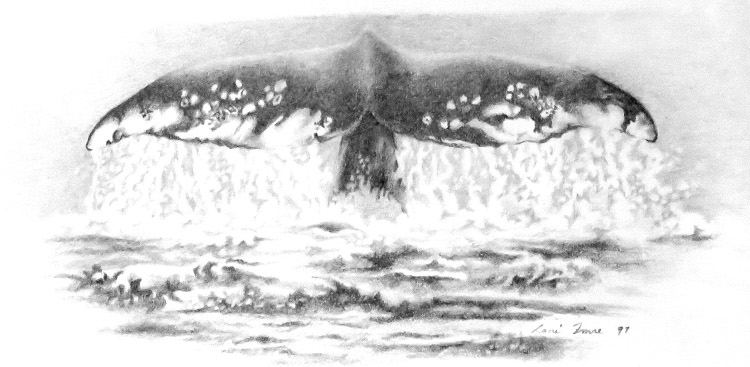

The most moving of the beautiful things were the flukes of a great whale sliding gracefully beneath the sea. My daughter Diana had the flukes tatooed on her ankle shortly after Jeff died; his initials, JAL, were inscribed beneath. Among its several symbols I see a strong, yet vulnerable animal returning to the environment of its birth, its life, its joys and its end as it moves through the cycle which all of us ultimately must.

If we listen to our inner selves, allow the world to carry us along for awhile without having to control it, absorb love given by family and friends and somehow realize time is our greatest ally, I believe most of us will come out of our grief intact. Eventually enough time passes to allow joy to return, perhaps more profoundly than ever. Time allows us to forget for ever-increasing periods; it provides desperately needed respite.

Fourteen months after Jeff died I recorded in my journal:

This month I completely missed the 18th! My God, how could I? But perhaps that is a good sign. Perhaps I really am healing now.

And just a few weeks later while enjoying the exhilaration of cross country skiing with my daughter in Manning Park, I recall panting to myself as we chugged along one of the trails, “If life is a competition, I’m winning!”

Time, love and the great outdoors were healing me.

I won’t tell you that every day, week and month since then has been an “up” time. Most certainly not, for my ghosts continue to visit. But for the most part they come more softly now, and often remain for only a short period.

After sixteen months, time had allowed sufficient healing for Carol and me to “get away from it all” in Hawaii. A year earlier we couldn’t have done that. Our misery would have spoiled the beauty of the islands. We didn’t go there to forget; one cannot do that. But we did go to reconnect, something very necessary for couples who suffer our tragedy.

Grief puts a terrible strain on marital relationships. From the moment a child dies, life is forever altered. Statistics show that many marriages fail under these circumstances, but the ones that endure often are better than before. The tragedy of losing a child can strengthen, but it can also tear apart. One can only hope, and work very hard for the best.

By the time we went to Hawaii, our world which lingered in suspended animation for so long, was beginning to return. Real healing was happening. We were able to discuss Jeff’s life and death freely without unmovable melancholy; we were aware of the beauty of our surroundings; we assumed an attitude we were happier with. I noticed my sense of humour with my students was returning. Memory was on its way back. I was taking Jeff along on new adventures. Self-confidence that had completely left me for months was returning. I felt good about these things; they were signs of positive healing.

And much to my surprise, I was feeling grateful. Grateful that despite the months of turmoil, my wife and our two surviving adult children seemed to have our lives intact, at least as intact as circumstances allowed. Grateful also for the twenty-five years. They could have been far fewer.

During that period I wrote a poem I would return to many times, for there were to be days I would require assurance I was surviving.

Taking Charge

For your mother it has been her books and her emerging faith.

For me, the writing.

In concert with family and friends, these have sustained us,

Been our communion, and quite frankly, our salvation.

Those early months after your death seem a long time past,

The confusion of emotions so baffling

As we struggled to comprehend our new lives.

Most everything had seemed ordered, in place

As we lived our comfortable routines

And looked expectantly to the future.

We seized our opportunities as presented.

Probably would have taken advantage of more

Had we been granted the luxury

(No, not luxury)

Of seeing into the future.

But thankfully there are few regrets,

And little guilt.

Many of the darkest moments are behind (I can only hope)

For none of us wants to entertain the demons

That plagued so many days and nights—

Especially the nights.

Fatigue leaving us virtually defenceless

Permitting self doubt, bizarre thoughts, visions

And at times, wallowing.

But some taking charge returns, Jeff,

Some sense that we can regain control of our lives

As the footing solidifies and we begin our halting ascent

From the black recesses.

Assuredly the darkness returns, and will,

For your death continues to occupy our waking moments,

Colour most everything we undertake.

But there is a softening,

A one day at a time returning to mainstream life

Once incomprehensible.

We seized our moments with you as we had them

Before…

After, we are doing so again.

But in such a different fashion

Now that we have ridden the roller coaster

And been ambushed by the valleys.

We have put our future on hold,

Appreciating each day for itself now.

Becoming aware we can survive this,

Are surviving this,

As we rediscover ourselves.

Hoping some good will come

Though God only knows.

I hope He does know, Jeff,

Has a plan, and will tell us about it.

Though He’ll have one hell of a time convincing me

The price fit the product.

May ‘96

But between December 18, 1994 and “Taking Charge,” existed a plethora of events and misery which had to be endured and worked through. Before we can emerge whole, each of us must give death its due. To deny grief its existence is inconceivable. To forbid it, to suppress our emotions, is folly.

I compare my healing to the path taken by the roller coaster I rode as a kid at the Pacific National Exhibition in Vancouver. The exhilaration of being at the top after a grinding climb was quickly replaced by the terror of plummeting straight down. While a crash at the bottom never occurred at the PNE, it occurred every time on my emotional roller coaster. Every high was inexorably followed by a low, and it wasn’t until I had ridden several times that I was able to anticipate the eventual outcome and be somewhat prepared for the crashes. I began to fear the highs because I knew what followed.

Eventually, however, I learned how to approach moments that brought a measure of happiness. I also learned not to throw myself with reckless abandon at opportunities to enjoy life, but to approach them gradually, allowing myself measured amounts of happiness thereby cushioning the lows. For example, after two or three visits from afar by good friends, my wife and I knew we would tell others who wanted to come we would love to have them, but from experience we learned staying for a few days was more beneficial than having them for a week or more. Each up had its corresponding down; we tried to minimize the duration of the latter.

I know I will never get over Jeff’s death, but I know also I am getting a second chance at life. After feeling dreadful for so long, I am in awe of this new state that allows me to function with renewed enthusiasm. Life takes on a holding pattern, a time for us to recover. A time when we are on the mat busted, unable to get up. I recognize very clearly each of us heals in our own way and in our own time after losing someone we love. But I believe emphatically that with help and time, we will recover and find much to live for. In the meantime we must pay the price death exacts.